Manuel Bromberg peintre aux armées

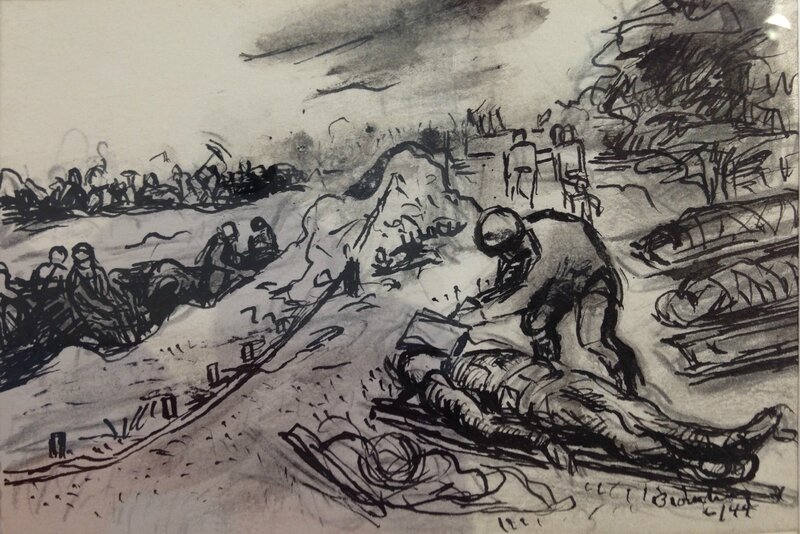

Manuel Bromberg est désigné en 1943 pour être l’un des 18 artistes à devenir peintre aux armées au sein de la prestigieuse armée américaine. Le 9 juin 1944, il débarque à Omaha qu’il compare à l’enfer de Dante, enfer vécu trois jours plutôt par des milliers de GI’s. Dés le début, il photographie, prend des notes, réalise des croquis sur des petits carnets, sur la moindre feuille de papier.

Vous pouvez découvrir quelques dessins au sein de l'exposition temporaire du Mémorial de Caen : "les 100 objets de la bataille de Normandie"

Vous trouverez ci joint un extrait de l'article du Guardians de 2004 écrit par Adam Levy. Manuel Bromberg aurait inspiré Steven Spielberg pour le film "Save private Ryan"

When Manuel Bromberg came ashore at Omaha beach in June 1944, he was armed with a green sketch pad and a Leica camera around his neck. He was one of a select few, a member of the US war artist unit. "It was an impossible sight. Bodies were still floating in the water. It was a combination of Dante's Inferno and the biggest junkyard ever seen."

Over the course of the next days, he tried to capture what he saw. Unlike the photographic images of Omaha beach taken by Robert Capa, which were to become the inspiration for the first 20 minutes of Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan and have gone on to shape our collective visual memory of D-day, Bromberg's images are of a very different order. With their informal, almost snapshot quality, their intimacy and their attention to the wreckage of battle, they speak to another side of war.

"Capa was very brave, but foolishly brave," says Bromberg. "I had a wife and child back home, and I'm a city boy, which means I know danger when I see it. And I know when you are in a spot when you might get killed. So I didn't do like Capa."

These photographs differ from Capa's images in another way, too. They have been lying in a cardboard box in Bromberg's painting studio in Woodstock, New York State, for the past 60 years. They have never before been published.

Bromberg was one of 18 artists handpicked by the war artist unit in 1943 to, as his letter of commission grandly stated, record "the impact of the war on you, as an artist, a human being. One has in mind Goya's Horrors Of War." Three artists were assigned each of the six theatres of war. Bromberg had originally asked to be assigned to India, Burma and China, because those places had sounded exotic to him. He was sent to England instead.

For 10 months he sketched and drew the pilots, supply personnel and mechanics of the US air force while they worked on their bases in England and Ireland. While on leave in London, he took tea with the art historian Kenneth Clark at his house on Hampstead Heath. He also met the British artists who were a part of the British war artist unit - Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and John Piper among them. It was a heady and exciting time, and Bromberg was much impressed by the fortitude and cheerfulness of his British hosts as the V-2s fell on London.

Then came the orders to begin Exercise Fox, the secret training for the Normandy invasion. Bromberg was sent to Slapton Sands, where he sketched the military exercises and spent time drinking in the local pubs. Finally, in June 1944, he crossed the channel.

He arrived on Omaha beach after the most brutal fighting had already taken place. Nevertheless, he was overwhelmed by what he saw. "Here I was with all this debris of the war and bodies and destroyed homes and destroyed bunkers and destroyed minefields and hedgerows and orchards - it was this enormous visual tapestry. How the hell are you going to handle it?"

His solution was to gather notes, visual notes. Wielding his Leica much as a journalist would use a notebook, Bromberg went about gathering details, photographic images that he envisioned using later in his paintings: the twisted forms of the German defences, the skeletal outline of blasted trees against a blank sky, a soldier with a shell lodged in his gut.

As a result, his photographs do something different from either adrenaline-stoked shots of battle or the more standard war photographs that fill the pages of most military history books, those informational but rather banal images of helmeted troops accompanied by tanks and jeeps.

Bromberg's images are both more consciously aesthetic and more particularly human. Aesthetically, he wasn't interested in depicting heroics, but rather the impact that the forces of war had unleashed on both material and on the human body. He found the crushed and shattered hull of a ship "aesthetically beautiful as a result of violence", which was probably not what the army had in mind when it sent him into battle.

While visiting a makeshift evacuation hospital set up on the bluffs over the beaches, Bromberg found himself scanning the dead and dying in search of the telling detail. "I was busy looking at the tents and the men lying flat on the ground, the various stages of the bandages." What he found was a soldier outstretched in an almost painterly pose, looking both vulnerable and serene. The scar on his chin and the ring on his finger lend the figure a poignant specificity.

Trying to understand and represent the devastation of war from a visual artist's point of view, rather than from a military or even a journalistic perspective, gave Bromberg a distinctive take on things. "The US army signal corps photographers were very brave guys. They were right up there in the front line in a way that I wasn't. But they were ordered to take certain kinds of images. They walked past the obvious. They were doing the apparent image of war. But the obvious contains more than your senses can bear."

Bromberg was operating under different assumptions. "I was thinking pictorially. I was thinking not just about the subject matter, but also what was evoked." He also felt burdened by the responsibility of his assignment; the words of his commission made him anxious and depressed. "That's scary right away, to be told to do like Goya."

Sixty years later, Bromberg feels that he never was able satisfactorily to depict what he experienced on the beaches of Normandy. But, on the other hand, he's proud that he was able to capture an overlooked dimension of the war, that his photographs might help us to shade in the memory of Normandy with slightly different meanings. "Omaha beach images are set to certain high points," says Bromberg. "I have photographs of GIs cutting other GIs' hair on the beach. You don't see that in Spielberg."

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F9%2F1%2F913300.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F08%2F1017141%2F113379056_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F89%2F15%2F1017141%2F113324571_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F17%2F1017141%2F112594085_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F14%2F1017141%2F111729136_o.jpg)